“Philosophy and science share the tools of logic, conceptual analysis, and rigorous argumentation. Yet philosophers [and artists] can operate these tools with degrees of thoroughness, freedom, and theoretical abstraction that practising researchers often cannot afford in their daily activities.” (Laplane et al, 2019).

There are many artists that depict scenes from the Cosmos, or meld Art and Science, widening the appeal and accessibility of Astrophysics to a far wider audience than space-enthusiasts.

Furthermore, interconnectedness is widely discussed across fields of Natural History, Science, Mathematics and Philosophy. But all of these are working within the siloed perimeters of their own field.

In this respect, I feel that my topic sits within unchartered territory in that it takes Cosmology one step further by revealing the interrelated threads that connect these fields, and why it matters.

My reading has therefore taken me far and wide, straddling myriad topics, disciplines, and fields which, I believe, are all interconnected and should therefore not sit separately as siloed disciplines. The full list of texts can be found in the Bibliography section of my Contextual Essay submission for unit 1.2.

The key texts that are informing my current work, sorted here by author’s surname:

- Origin of the Species by Charles Darwin

- The Accidental Species by Henry Gee

- Staying with the Trouble by Donna Haraway

- A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

- Gaia and Novacene by James Lovelock

- The Ecological Thought by Timothy Morton

- Two papers around the topics of Deep Ecology by Arne Næss

- Matters of Care by Maria Puig de la Bellacasa

Herewith a brief summary of my critical response to each of these texts:

Origin of the Species by Charles Darwin

My biggest takeaway from reading selected parts of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) was around his central argument that species have evolved fairly randomly over millions of years by way of natural selection and descent with modification. This means that our anthropocentric view that was as humans belong at the top of the food chain because we are somehow special or different or superior is incorrect. Furthermore, descent with modification reveals that it is not a case of ‘survival of the fittest’ in the way that we have come to understand it. It is generally accepted that ‘survival of the fittest’ intimates that species – including humans – have adapted to their environment as a response to that environment. If we were truly the fittest version of ourselves, our species would not have multitudes of ‘left-over’ redundancies such as: men have nipples, babies in vitro can be seen to have rudimentary gills which are then reabsorbed, we can’t run particularly fast because we’ve become bipedal, and our wisdom teeth can hardly fit into our jaws. Instead, descent with modification shows that a certain degree of genetic differences/variations will always exist, and it is those that are best adapted to the current environmental conditions that are more likely to survive and thrive. For example, an ancient elephant species that are born with more hair on their skin than others – these would be more adapted to colder climates, and so when for example, ice age begins, is is those hairier members of the species that are more likely to thrive and mate, and so this ‘hairy gene’ is the one that continues… and then we get wooly mammoths! Evolution is therefore driven by natural selection. (Darwin, 1859)

The Accidental Species by Henry Gee

Evolutionary Biologist Henry Gee offers a posthumanist view of evolution which closely mirrors my own – that human exceptionalism is an anthropocentric misconception. As humans (and archeologists), we talk about needing to find ‘the missing link’ – that set of fossils which help us to understand the lineage of our species – as though it is a straightforward, singular process.

Instead, Gee shows us how evolution is more akin to a branching tree – some branches continue to become sub-branches, whereas others end closer to the trunk. He also reveals how unreliable and incomplete our fossil records are – how many other species have not been accounted for in the fossil records because their fossils didn’t survive?

The tree branch analogy shows us that evolution isn’t linear, and that evolution of all species happened by fairly random happenstance. Evolution is not looking for an end-goal or purpose. Rather, as is explained by Darwin in Origin of the Species, through descent with modification, natural selection and sexual selection, certain genetic traits have survived because they are better adapted to their environments. In this way, were environmental factors to have been different, there could have been countless other permutations that species would have appeared in.

Humans, like dinosaurs, are just one possible outcome of a much larger ongoing evolutionary story.

Staying with the Trouble by Donna Haraway

I adored and despised this text in equal parts, and felt like I needed to bring 100% of my brain to the reading in order to access 50% of what it was trying to tell me! Furthermore, I could not find this text in Dubai so ordered the ebook for my Kindle and I cannot recommend reading a text like this on a Kindle. The reading experience needs to be a lot more visceral – similar to the experience I had reading Matters of Care by Puig de la Bellacasa, where I needed to read armed with highlighters and pens, flipping backwards and forwards through the text to re-read certain sections.

Be that as it may, I took the main message of this book to heart and stayed with the trouble because it was well worth the trouble! Haraway offers a visionary way with which to view and approach the current environmental and social crises that we are faced with. This speculative work is all at once sometimes fact, sometimes art, sometimes philosophy, sometimes memoir, and offers us a blueprint on how to ‘stay with the trouble’ which means how to stay with the difficult ecological and social times in which we find ourselves, instead of putting our heads in the sand and staying blissfully ignorant.

One of my biggest takeaways from this book was Haraway’s idea of making kin. We understand kin as those friends and family that we know, and therefore care deeply about. Haraway’s idea of kin extends into posthumanism, where – because we are all interconnected and entangled – everything is kin including other species, other environments and other technologies. This idea has informed a lot of my own thinking around interconnectedness – we care about our kin, and so when we extend our matters of care to our extended boundaryless kin, we become more awake, more responsible, more empowered to make positive change… to make a difference.

If everything is our kin, we become a planetary species, and will take more responsibility of our shared custodianship of our planet.

A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

This complex read gave an excellent window into topics within astrophysics such as the theorised origin of the universe, space, time and black holes in a way that is more accessible to a wider audience than just astrophysicists. The work dips into philosophy and helps us to consider bigger existential questions like what is the nature of reality, and what is our place in the cosmos?

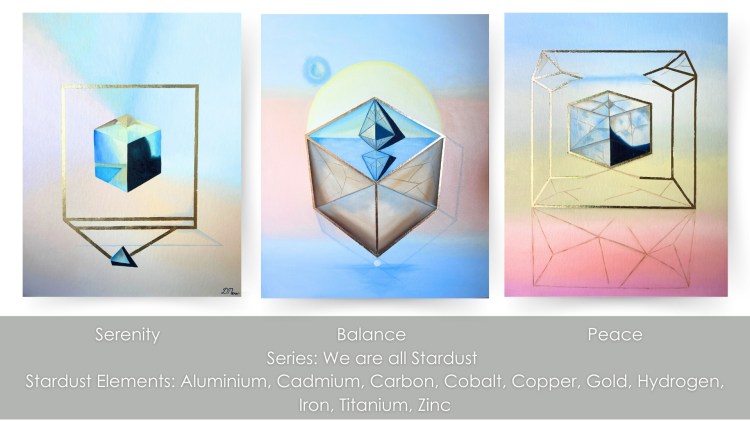

The book covers the origin of the universe including the Big Bang Theory, and this has spearheaded my main line of enquiry and my practice-based research methods. It is through this work on the origin of the universe that I learnt the story of the elements on our Periodic Table (most of which are stardust, and aside from the man-made ones, all of which were birthed as part of evolutionary processes in the cosmos).

Philosophically, Hawking argues that seeking the origins of the universe and its existence does not invoke the idea of God as he feels that science does not need a divine creator. Instead, the laws of physics explain a lot about the universe’s creation.

Whereas a lot of the other work that I am reading takes more of a philosophical stance, I found this book refreshing since it is rooted in Scientific Research and discovery.

Gaia by James Lovelock

Gaia by James Lovelock is a cautionary text that posits that the planet earth is not simply a planet on which many species and environments exist. Rather, the Gaia Hypothesis posits that earth is one single living, breathing self-regulating, ever-evolving entity capable of taking care of itself and making adaptations (and extinctions) as needed. Just as our human body can be seen as a universe within a universe, with multiple systems and indeed multiple species (bacteria, fungi and viruses) all living as one cyborg-style assemblage, earth can be seen as one entity floating in the universe with multiple systems and species all living as one.

Whilst the book has come under some criticism for anthropomorphism, I love this idea. The cautionary element of the book provides a strong ‘why’ behind why we should care about the environment: we are currently in our sixth mass extinction – according to Lovelock, these mass extinctions are Gaia’s way of self-regulating. Over millennia – and through the geological record, we’ve seen so many species go extinct, and as a species we should exercise caution because if we became too much of a burden on Gaia, Gaia would simply act to obliterate us and carry on as normal as has happened multiple times before.

Novacene by James Lovelock

In Novacene, Locklock continually moves between the idea that we have left the Anthropocene epoch and have now moved into the Novacene, and that we are still in the Anthropocene epoch but that it’s days are numbered because the writing (of the Novacene) is on the wall. I didn’t enjoy this noncommittal style and I was left not understanding which of these two were his personal stance on the matter. However, all in all, Novacene offers a fairly uplifting and upbeat view of the future, positing that hyperintelligence (AI) becoming self-aware isn’t necessarily a bad thing. He also presents an uplifting idea that AI is better equipped to deal with problems such as climate change than humans are.

Appleyard, B (2019) in the Preface of Novacene (Lovelock, 2019) states “Novacene is Jim’s name for a new geological epoch of the planet, an age that succeeds the Anthropocene, which began in 1712 and is already coming to a close. That age was defined by the ways in which humans had attained the ability to alter the geology and ecosystems of the entire planet. The Novacene – which Jim suggests may have already begun – is when our technology moves beyond our control, generating intelligences far greater and, crucially, much faster than our own. How this happens and what is means for us are the story of this book.”

Initial musings about this book:

One of Lovelock’s main ideas is that humans are the chosen species (Anthropocentrism). I do not agree with this and whilst it is, admittedly, mysterious, enchanting and uncanny that humans have evolved in complexity seemingly more than any other species, I don’t feel that that means that we are ‘chosen’ or ‘special’. Mine is a more post humanist view. However, no sense in throwing the baby out with the bathwater – I’m choosing to agree to disagree because much of what Lovelock writes does resonate with me.

Furthermore, I feel that this book could have been split into two entirely different texts: the first 60% of the book covers the Anthropocene – how we got to where we are now. It reveals a lot of fact and science-backed thought. The remaining 40% of the book is speculative. Lovelock spends this last part of the book teetering between the Novacene having already begun, and the Novacene about to begin, with many suppositions of what Cyborgs/AI would do and think once they ‘take over’. I didn’t love this last 40% – it felt possible, but at the same time fictionalised. I suppose that that is what Science is all about: theorising first, then setting out to prove or disprove.

I enjoyed that Lovelock bolts Novacene on to his seminal text Gaia, positing that AI is just another evolutionary process in Gaia’s becoming.

The Ecological Thought by Timothy Morton

Once aptly dubbed by a journalist ‘the Philosopher Prophet of the Anthropocene’, Timothy Morton’s deceivingly thin (but overwhelmingly meaty) text The Ecological Thought implores us to see ecology not as a discipline but as a way of thinking and a way of being in the world. Underpinned by the idea that everything is interconnected and interdependent, when we recognise this, we are thinking ecologically. When we think ecologically, we are going deepr than merely acknowledging environmental issues, but we are also recognising and taking ownership of our part in the current state of our environment and indeed the climate crisis of our planet. Morton argues in favour deep entanglement – the idea that everything – humans, non-humans, material and non-materials things are entangled and interconnected deeply. This book is a call to us rethinking our place in the world.

A lot of Morton’s thinking around moving away from anthropocentrism towards posthumanism, recognising that non-human beings and non-beings also have agency and importance, has shaped the way that I think about my own place in the world. As inaccessible as the writing was in this book, I so enjoyed the message threaded within that I bought and read another three books by Timothy Morton: All Art is Ecological, Being Ecological, and Deep Ecology.

Various Deep Ecology essays by Arne Næss

Næss introduces us to the idea of Deep Ecology vs. Shallow Ecology. Shallow Ecology is the type of ecological thinking that most people would think about when they think about climate change and the current state of our environment. From a Shallow Ecology standpoint, the reasoning behind why we should care about environmentalism and climate change is because of the human inconveniences that these cause. Næss critiques and criticises this thinking, in favour of what he has named Deep Ecology.

In contrast, Næss argues that Deep Ecology is more radical and philosophical, calling for a fundamental shift in the way that our species relates to the environment. It is also a call to move away from anthropocentric thinking towards a posthumanist view where we realise that all living things, whether ‘useful’ to humans or not, need to be taken into consideration when thinking about the world and its longevity. Similar to Puig de la Bellacasa, this text is a call to extend our matters of care to all living things, towards nature and to the environment. Like Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis, Næss argues that we need to take a longer range view of the wellbeing of the entire planets.In The Ecology of Wisdom (2008), Næss expands further on his idea of Deep Ecology, connecting ecological concerns with human wisdom, whilst also emphasising the importance of ecological thinking in our everyday lives. (I can see where Morton got a lot of his Deep Ecology ideas from!) Perhaps most inspiring about Næss’ work is that he practiced what he preached, living out his ideas in an off-grid wood cabin atop a mountain range.

Matters of Care by Maria Puig de la Bellacasa

I read this book cover to cover, armed with highlighters and pens, and I’m afraid it is dog-eared and annotated to the hilt – which is okay, because I am unlikely to ever give it away.

Puig de la Bellacasa urges us to re-think matters of care. In this book there are many references to Latour’s Matters of Concern (Labour, 2005), and I have read these too – I feel that they are essentially speaking about the same topic and somewhat splitting hairs when it comes to naming conventions. The sentiment is the same: we need to think deeply about things in order to extend our care to things possibly previously unthought about (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017).

The central theme is around ethics – it is more ethical to really try to take all aspects and angles into consideration. For example, if I am making a piece of art, and I want to think about the ethics around that piece, I should not limit my care to ensuring that the subject matter depicted is not unethical. I could also think about where my art materials come from (are they local? Are they shipped in? Flown in? Where are they flown in from? Have they come from far? Is there a closer place I could source these, or source locally in order to minimise the carbon footprint of importing? Where and how are my art materials manufactured? Do they come from places that have unfair labour practices? Do they contain chemicals that are harmful to the environment, and if so, are there safer alternatives? Could I instead make something entirely different from reused items that take away from landfill instead of adding to it?

When I dispose of the unused or unneeded items (paper scraps; empty paint tubes), am I doing so responsibly? Can anything be reused or recycled? Are there any chemicals contained therein that might be harmful to the environment and aquatic life? If so, what is the most environmentally responsible way to dispose of them?)

I really liked how Puig de la Bellacasa presented speculative imagined futures where care is central to everything from politics to environmental concerns. The biggest takeaway for me was that when we think about what we should care about, we need to extend and expand our matters of care to more-than-human worlds. I could not agree more: my research and reading is pointing to everything being connected and entangled, sometimes in ways that we don’t yet understand. But if everything is connected and entangled, then everything has an impact on everything else, and we should therefore care about that and get into the habit of thinking deeply about everything upstream and downstream of our thoughts and actions. (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017)

References:

Darwin, C. (1859) On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. 6th ed. London: John Murray.

Gee, Henry (2013) The Accidental Species – Misunderstandings of Human Evolution. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Kindle Ed [ebook]. North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Hawking, S. (1988). A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes. London: Penguin Random House.

Laplane, L et al (2019) Why Science Needs Philosophy. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1900357116#:~:text=Philosophy%20and%20science%20share%20the,afford%20in%20their%20daily%20activities.(Accessed 22 October 2024)

Latour, B (2005) What is the Style of Matters of Concern? Available at: http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/97-SPINOZA-GB.pdf (Accessed 12 August 2024)

Lovelock, J. (1979). Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lovelock, J (2019). Novacene – The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence. London: Penguin Books

Morton, T. (2010). The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

Næss, A. (1973) ‘The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movements. A summary.’ Inquiry 16 (1–4): 95–100. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00201747308601682 (Accessed 2 September 2024)

Næss, A. (2008) The Ecology of Wisdom: Writings by Arne Næss. Berkeley: Counterpoint.

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.